lego-builder-divine-connection-1.jpg

David Jungheim, chief artist and co-curator of the exhibit “Brick Upon Brick: Creativity in the Making,” poses for a portrait at the exhibit located in the Harold B. Lee Library on the campus of Brigham Young University in Provo, Utah, on Wednesday, July 3, 2024. Jungheim built the Joseph Smith Memorial Building, left, and Salt Lake City Temple, background, out of LEGO, and the exhibit also features the work of other artists in the medium. Photo by Isaac Hale, courtesy of Church News.Copyright 2024 Deseret News Publishing Company.This story appears here courtesy of TheChurchNews.com. It is not for use by other media.

By Kaitlyn Bancroft, Church News

David Jungheim has an eye for detail.

The doorknobs on his LEGO Joseph Smith Memorial Building — built from 97,000 LEGO bricks — are stainless steel-colored where their real counterparts are steel-colored, and brass-colored where the real ones are brass-colored.

His LEGO Temple Square Assembly Hall — built from 16,300 LEGO bricks — features asymmetrical stained-glass windows, a nod to when the real windows were removed for restoration and then re-installed in the wrong order.

And his LEGO Salt Lake Temple — built from 25,000 LEGO bricks — features a custom engraving of the words “Holiness to the Lord — The House of the Lord,” designed to match the letters’ font and spacing as closely as possible.

lego-builder-divine-connection-2.jpg

Lainey Black, 12, of Elk Ridge, Utah, checks out the Salt Lake City Temple in LEGO form at the exhibit “Brick Upon Brick: Creativity in the Making,” located in the Harold B. Lee Library on the campus of Brigham Young University in Provo, Utah, on Wednesday, July 3, 2024. Photo by Isaac Hale, courtesy of Church News.Copyright 2024 Deseret News Publishing Company.It’s all part of capturing the “soul” of whatever building Jungheim is recreating through LEGO. He especially loves it when people who are familiar with the real buildings comment on the accuracy of his creations, he said.

But Jungheim’s meticulous research — sometimes up to two years of reading history, studying blueprints and visiting the sites themselves — isn’t simply to impress. As he’s learned about how the early Saints built the Salt Lake Temple and related buildings, “it’s really helped me to understand sacrifice, and what it means to be a member of the Church.”

Now, he hopes his work can help other Latter-day Saints have similar spiritual experiences.

lego-builder-divine-connection-3.jpg

The Salt Lake Tabernacle is displayed in LEGO form at the exhibit “Brick Upon Brick: Creativity in the Making,” located in the Harold B. Lee Library on the campus of Brigham Young University in Provo, Utah, on Wednesday, July 3, 2024. Photo by Isaac Hale, courtesy of Church News.Copyright 2024 Deseret News Publishing Company.Four of Jungheim’s largest LEGO creations are currently on display at Brigham Young University’s Harold B. Lee Library, part of the free “Brick Upon Brick: Creativity in the Making” exhibit in the library’s Special Collections section.

Through July 20, the public can view Jungheim’s large LEGO replicas of the Salt Lake Temple, the Temple Square Assembly Hall, the Salt Lake Tabernacle and the Joseph Smith Memorial Building.

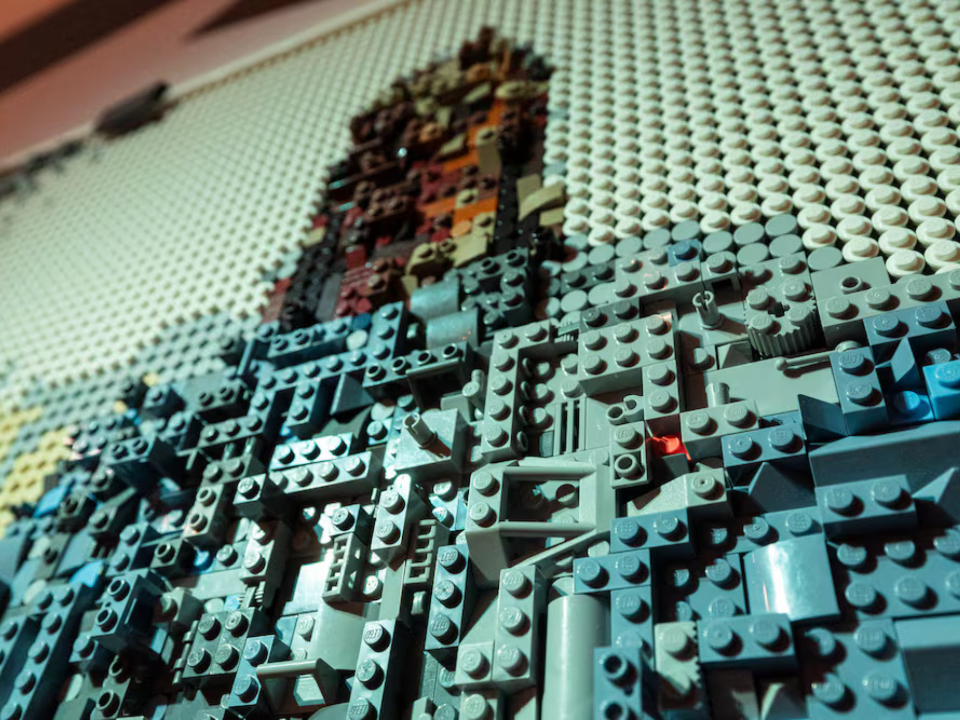

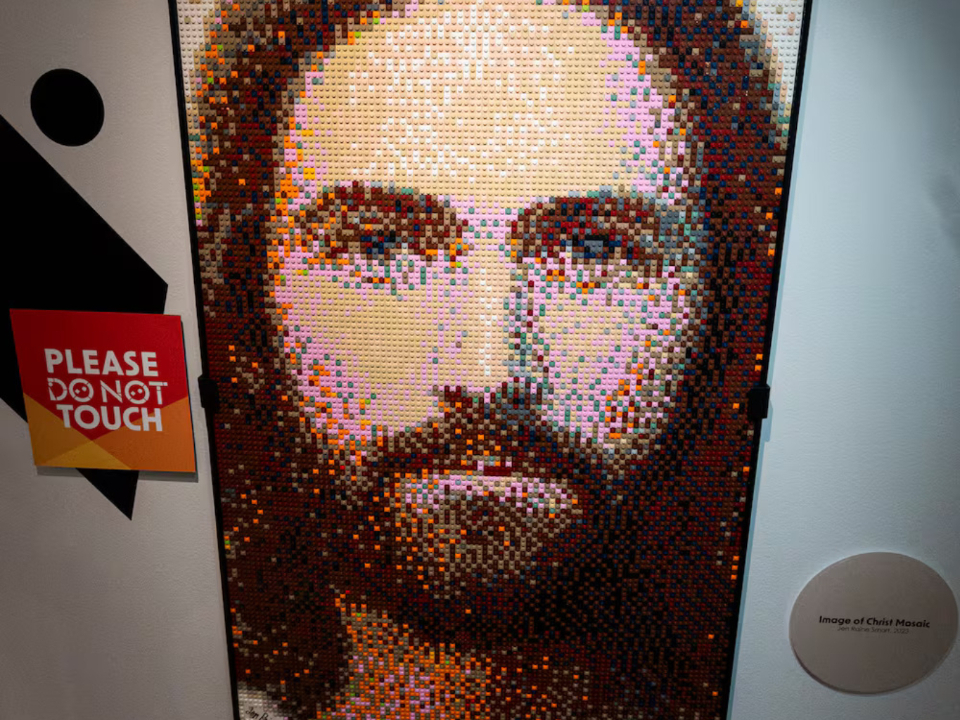

A number of other LEGO artists contributed to the exhibit as well, such as Jen Raine Smart’s “Image of Christ” LEGO mosaic, or Jackson Wehrli’s LEGO recreation of Harry Anderson’s famous painting “The Second Coming.”

And while the displayed artwork is for looking only, big and little hands alike will find plenty of LEGO bricks to build their own masterpieces with.

Trevor Alvord, a BYU Special Collections curator, said when the library did a smaller-scale LEGO exhibit in 2015, the goal was to help people see LEGOs as an artform rather than as just toys. The “Brick Upon Brick” exhibit grew out of that success, he said, and is now taking the idea a step further: introducing LEGO bricks as vehicles for sincere spiritual experiences.

The exhibit especially takes inspiration from then-President Dieter F. Uchtdorf’s October 2008 general conference talk, “Happiness, Your Heritage.”

“The desire to create is one of the deepest yearnings of the human soul,” he said at that time. “No matter our talents, education, backgrounds, or abilities, we each have an inherent wish to create something that did not exist before.”

Alvord said even following instructions to build something from LEGO is an act of creation.

lego-builder-divine-connection-4.jpg

Pieces of LEGO comprising the “The Second Coming Mosaic” are displayed at the exhibit “Brick Upon Brick: Creativity in the Making,” located in the Harold B. Lee Library on the campus of Brigham Young University in Provo, Utah, on Wednesday, July 3, 2024. Photo by Isaac Hale, courtesy of Church News.Copyright 2024 Deseret News Publishing Company.“You’re still exercising not only that God-given agency, but that inherent nature of who we are as divine children of the Ultimate Creator,” he said.

Jungheim agreed with Alvord, adding that he’s become emotional at times handing off large projects to clients because he’s poured so much of himself into his work.

He hasn’t always considered himself an artist, he said, but in the time since his first LEGO Salt Lake Temple gained widespread attention, his mindset has shifted.

“We are offspring of the most creative being in the universe, and it’s in our nature to want to create and not just consume,” Jungheim said, adding, “I think it provides us happiness and connection to the divine and to the Savior to be creative.”

lego-builder-divine-connection-5.jpg

Wesley Whitehead, 11, of Lehi, adds to a community mosaic of LEGO at the exhibit “Brick Upon Brick: Creativity in the Making,” located in the Harold B. Lee Library on the campus of Brigham Young University in Provo, Utah, on Wednesday, July 3, 2024. Photo by Isaac Hale, courtesy of Church News.Copyright 2024 Deseret News Publishing Company.Life of a LEGO Builder

Jungheim received his first LEGO set at age 4 while his family lived in Germany, he said.

He recalled his childhood excitement the year that the LEGO company released slanted roof pieces. He built his first custom LEGO house with those pieces, he said, then wrapped it up, hid it under the kitchen sink and gave it to himself for Christmas.

Jungheim’s love for LEGO followed him through military service and various positions at BYU, including with the ROTC and the Marriott School of Business. He’s currently the space management coordinator for BYU, overseeing where and when the school’s many young single adult wards meet on campus.

His first major LEGO project, the Salt Lake Temple, started while he was still in flight school. Jungheim recalled sitting in the back of sacrament meetings, sketching building designs on graph paper. He worked on the project on and off for the next nine years, through a deployment to Afghanistan, building a house and attending graduate school.

But when he finished in 2012, the project took off — showcased in the BYU Store and later in BYU’s 2015 LEGO display. He’s since built a second LEGO Salt Lake Temple (much faster than the first, Jungheim said, partly because he used software to design it) as well as the other Temple Square buildings now displayed at BYU.

He also started Inspired Bricks, a business that’s helped him connect with clients who want custom LEGO builds. He’s now done nine commissions in the last eight years, he said.

lego-builder-divine-connection-6.jpg

The Temple Square Assembly Hall is displayed in LEGO form at the exhibit “Brick Upon Brick: Creativity in the Making,” located in the Harold B. Lee Library on the campus of Brigham Young University in Provo, Utah, on Wednesday, July 3, 2024. Photo by Isaac Hale, courtesy of Church News.Copyright 2024 Deseret News Publishing Company.Jungheim said the time and number of LEGO bricks required for large projects varies, but he averages around one big build a year, using between 22,000 and 97,000 bricks.

Some projects are more challenging than others — like when he built the Salt Lake Tabernacle’s round roof, and ran into the same structural engineering problems that the original builders faced. Eventually, he used their solution: internal trusses that are almost identical to their real-life counterparts.

Every Piece Matters

So far, the “Brick Upon Brick” exhibit has been an enormous success for BYU’s library. Alvord said while he can only speak for the exhibits he’s helped curate, the LEGO display has seen over double the visitors that an exhibit typically gets — over 42,000 people compared to an average of 20,000.

More important than the number of visitors, however, has been the patrons’ experience. Alvord recalled one boy looking at the to-scale LEGO Washington D.C. Temple displayed just outside the main exhibit, then turning the corner and excitedly shouting, “There’s more, there’s more!”

Alvord also recounted his 4-year-old son’s reaction to the LEGO mosaic portrait of Jesus Christ: “I’m not going to touch that, because that is Jesus, and it is beautiful.”

lego-builder-divine-connection-7.jpg

The “Image of Christ Mosaic” is displayed in LEGO form at the exhibit “Brick Upon Brick: Creativity in the Making,” located in the Harold B. Lee Library on the campus of Brigham Young University in Provo, Utah, on Wednesday, July 3, 2024. Photo by Isaac Hale, courtesy of Church News.Copyright 2024 Deseret News Publishing Company.Because the artwork was in a medium that his son understood — LEGO — he was better able, in his childlike way, to recognize the glory of an image of Christ, Alvord said.

“We have this amazing culture behind who we are as members of the Church, and … we’re embracing it in any kind of medium, any kind of way that we can to share our talents, to share our testimony with others,” he said.

He also noted that “every little piece” matters when building with LEGO, even when the pieces are imperfect.

“No matter how imperfect that piece might be or seem, it is still needed to create something bigger, something more holistic,” Alvord said. “And to me, that is also another parallel to the gospel. … No matter how imperfect we might be, no matter how we might feel alone, we are still needed to build this Kingdom of God.”

lego-builder-divine-connection-8.jpg

The Book of Mormon is displayed in LEGO form at the exhibit “Brick Upon Brick: Creativity in the Making,” located in the Harold B. Lee Library on the campus of Brigham Young University in Provo, Utah, on Wednesday, July 3, 2024. Photo by Isaac Hale, courtesy of Church News.Copyright 2024 Deseret News Publishing Company.

lego-builder-divine-connection-9.jpg

Various works of LEGO art are displayed on a community mosaic at the exhibit “Brick Upon Brick: Creativity in the Making,” located in the Harold B. Lee Library on the campus of Brigham Young University in Provo, Utah, on Wednesday, July 3, 2024. Photo by Isaac Hale, courtesy of Church News.Copyright 2024 Deseret News Publishing Company.

lego-builder-divine-connection-10.jpg

The angel Moroni stands atop the Salt Lake City Temple in LEGO form as “The Second Coming Mosaic” is displayed in the background at the exhibit “Brick Upon Brick: Creativity in the Making,” located in the Harold B. Lee Library on the campus of Brigham Young University in Provo, Utah, on Wednesday, July 3, 2024. Photo by Isaac Hale, courtesy of Church News.Copyright 2024 Deseret News Publishing Company.

lego-builder-divine-connection-11.jpg

David Jungheim, left, chief artist, and Trevor Alvord, right, both co-curators of the exhibit “Brick Upon Brick: Creativity in the Making,” pose together for a portrait at the exhibit located in the Harold B. Lee Library on the campus of Brigham Young University in Provo, Utah, on Wednesday, July 3, 2024. Photo by Isaac Hale, courtesy of Church News.Copyright 2024 Deseret News Publishing Company.Copyright 2024 Deseret News Publishing Company.