When it comes to Latter-day Saints and Missouri in the 1830s, thoughts often go to the infamous 1838 extermination order issued by Governor Lilburn W. Boggs. A less familiar but more redeeming story, however, is that Latter-day Saints had friends on the other side of the state. St. Louisans defended Latter-day Saints, and the city played a key role in their later migration to Utah.

| Temple Square is always beautiful in the springtime. Gardeners work to prepare the ground for General Conference. 2012 Intellectual Reserve, Inc. All rights reserved. | 1 / 8 |

Downloadable video: B-roll | SOTs

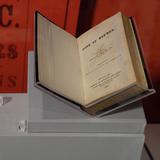

This history, along with many others from the westward expansion of the United States, is being told at the renovated Gateway Arch Museum in St. Louis. The 40-year-old museum, located under the iconic arch, has undergone a state-of-the-art update for its aging materials and general history of the American West. The new exhibitions chronicle 200 years of history with valued artifacts and audiovisual materials and is focused specifically on the city’s role in the nation’s westward growth.

“We're very, very excited about our new museum experience,” says Bob Moore, a historian with the U.S. National Park Service. “It’s something that people will enjoy on a lot of different levels.”

Moore teamed up with local Latter-day Saint historian Thomas L. Farmer to help tell the Church’s largely unknown St. Louis story at the museum.

“Bob told me that the Mormon story is something we have to tell at the new arch museum,” Farmer says. “Bob Moore is a true friend. He’s made this project possible. It’s been a joy. I couldn’t have asked for better people to work with. They wanted the true story told, which was exciting, and that’s what we gave them.”

Moore, the author of eight books and a park service historian since 1991, said it was interesting and surprising to learn the positive side to the Latter-day Saint story in St. Louis.

“Most of what I had known about the Mormon faith and Missouri was very negative,” Moore said. “It was the idea of the extermination order and Lilburn Boggs and all of that. And then I started to learn, well, no, that wasn't the case here in the eastern part of the state. [Latter-day Saints became] a vibrant part of the community. And there's no negative publicity about them. There's not the kind of thing you might see in an opposition newspaper, ‘Oh, those dirty people are here in town.’ It was always this really positive thing that we have a large number of these people here, they're welcome in the community and they've been very helpful.”

The History

In 1831, Joseph Smith, the first prophet of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, told Church members that Independence, Jackson County, Missouri, was to be the gathering spot for the Church. The influx of members to the county raised concern among area settlers. Many Latter-day Saints were anti-slavery, worshipped differently and proved a formidable voting bloc. Locals ordered over 1,000 members to leave. Church leaders were unsuccessful in their attempts to seek protection from the courts. Mobs drove Church members out of the area. In 1834, Joseph Smith and approximately 200 armed men, called the Camp of Israel, or Zion's Camp, arrived to protect the members. A storm prevented the confrontation and the camp was later disbanded.

Latter-day Saint refugees found quiet in Clay, Caldwell and Daviess Counties. By 1838, Far West had become Church headquarters with homes, hotels, a printing house and a school. But the peace was temporary. Violence erupted in Gallatin in August 1838, when members were prevented from voting. Mob raids began, and Elder David W. Patten, a member of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles, was killed. The exaggerated rumors about Church members ultimately led to the extermination order from Gov. Lilburn W. Boggs in 1838. At least 17 men and boys were killed at Hawn's Mill by an unauthorized militia.

The St. Louis community was opposed to these actions and defended the Church in the press in 1838. During this difficult time, Latter-day Saints sought employment and protection in St. Louis. A member of the Missouri legislature presented a petition to state officials requesting security for Latter-day Saints. Only a minority spoke in favor of the petition—but among them were all the government representatives from St. Louis.

“Although Governor Boggs’ order was enforced in northwest Missouri, no Latter-day Saints were expelled from St. Louis, and St. Louis citizens held several fundraising meetings to aid the Mormon exiles in their dire condition,” Farmer and coauthor Fred E. Woods of Brigham Young University write in summer 2018 edition of “Confluence,” a scholarly publication in St. Louis.

When Nauvoo, a city Joseph Smith founded in Illinois in 1839, fell in 1846, approximately 2,000 Saints came to St. Louis. It was a place, Farmer and Woods write, that “emerged as a city of refuge on the trail to Utah, a haven where Mormons could practice their religion without persecution.” Then, when those Saints were ready to go west, they could organize a company and head to Utah.

“Immigrants arrived here [and] would change steamboats and stay for hours, some for months, others for years, enjoying the sanctuary of the city of St. Louis,” Farmer says.

By June 1857, the Church stopped using St. Louis as a safety net for Latter-day Saints because a cholera breakout required emigrants be diverted to other areas. In the end, some 22,000 of the 70,000 early Latter-day Saint pioneers came to Utah through St. Louis between 1846 and 1857.