Assembly-Hall

Sister Kate Johnson and Sister DaMinikah Rodriguez give a virtual tour of Assembly Hall in Salt Lake City on Wednesday, April 28, 2021. Photo by Kristin Murphy, courtesy of Church News.All rights reserved.This story appears here courtesy of TheChurchNews.com. It is not for use by other media.

By Valerie Walton, Church News

On April 3, 1983, President Gordon B. Hinckley, then second counselor in the First Presidency and just off a weekend of general conference responsibilities, presided at the rededication of the Assembly Hall on Temple Square and offered the rededicatory prayer.

“For 100 years, this has been a place of worship and assembly,” he said. “Now we have made it possible for the building to serve the same function for at least another 100 years.”

He gestured to the intricate craftsmanship that highlighted the building’s interior. “This is a work of art and a work of engineering,” President Hinckley said. “The work has prepared for the future while preserving the integrity of the past. We ought to be proud of this.

Assembly-Hall

The interior of the Assembly Hall is pictured in Salt Lake City on Wednesday, April 28, 2021. Photo by Kristin Murphy, courtesy of Church News All rights reserved.“It is a sacred memorial to the past, with an eye to the future.”

Why an Assembly Hall?

“Public gatherings have been a part of Temple Square since almost the very beginning,” explained Emily Utt, historic sites curator for the Church History Department.

When the pioneers arrived in the Salt Lake Valley, one of the first buildings they erected was a bowery. Then on the southwest corner of Temple Square they built an adobe tabernacle called the Old Tabernacle. “That building is where they got to practice and figure out what designs would work for construction of the great tabernacle,” or what is now known as the Salt Lake Tabernacle, Utt said.

When the new tabernacle was completed, the old one became obsolete and would need to be torn down.

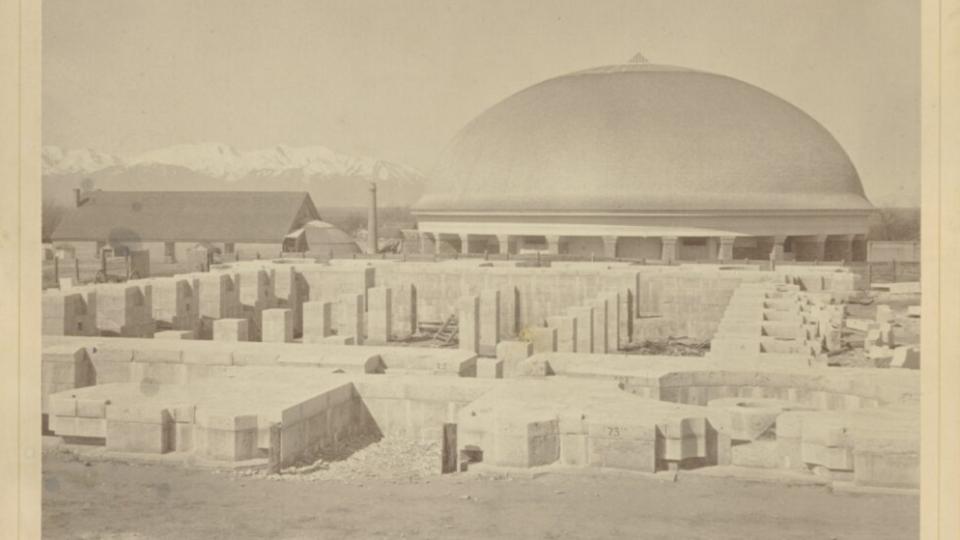

Assembly-Hall

In this photograph taken by Charles Roscoe Savage in 1873, the old Tabernacle and the new Tabernacle on Temple Square are shown, along with the foundations of the Salt Lake Temple in the foreground. The Assembly Hall would replace the old Tabernacle.2021 by Intellectual Reserve, Inc. All rights reserved.At the same time, stakes all over the Church were starting to build large, ornate buildings in the 1870s and 1880s, such as in St. George, Brigham City and Logan, Utah. These tabernacles were architectural statements that were forward thinking and up-to-date with current trends.

“And so the Salt Lake Stake wanted one of these big architectural statements,” Utt explained.

Brigham Young, President of the Church at the time, and Salt Lake Stake leaders decided to build one of these statements on Temple Square. On August 11, 1877, Young announced the construction of a new Assembly Hall that would hold 1,200 people and be warm even in winter. “Demolition of the old building begins the next day, and they start construction within a month, which is quick,” Utt said.

Assembly-Hall

The Salt Lake Assembly Hall in 1888.2021 by Intellectual Reserve, Inc. All rights reserved.Building architect Obed Taylor designed it in an on-trend, late Victorian Gothic Revival style with pointed spires and a medieval feel. Unfortunately, he died in 1881 before the Assembly Hall was completed.

The design of the Assembly Hall inspired at least two other “sister buildings,” as Utt put it. William Folsom, who Taylor joined architectural forces with for a while, designed the Provo Tabernacle, now the Provo City Center Temple. Another tabernacle in Coalville, Utah, was the other sister building.

“What’s interesting is that there are some innovations in this building that, had it been in another large US city, probably would have gotten some more attention,” Utt said. The Assembly Hall’s most innovative feature is its roof because of “the way that the tower and steeple is constructed. The design is a rather unusual feature in buildings of this type in the late 19th century.”

There is a common story that the stone used to build the Assembly Hall came from the refuse of the Salt Lake Temple. “While that is technically true, what makes it so interesting is the pieces they’re selecting,” Utt said. Cutting blocks out of boulders for the temple left perfectly useable, beautiful building stone. “They took these irregular shaped pieces that weren’t of the right size or shape to be used on the temple and built the Assembly Hall out of them.”

Assembly-Hall

A photograph taken in 1890 by Charles Roscoe Savage from the roof of ZCMI on Main Street in Salt Lake City, shows Temple Square including the Salt Lake Temple under construction, the Salt Lake Tabernacle and the Assembly Hall.2021 by Intellectual Reserve, Inc. All rights reserved.Expert stonemasons were called in to bring these irregular pieces of stone together into a building with clean lines and prominent mortar joints.

Missing Frescoes

The interior of the building received just as much care and attention as the outside. The walls and columns have been decorated with sego lilies and beehives. But one of the most unique features of the Assembly Hall was the frescoes that covered the ceiling.

Before the building was dedicated in 1882, 16 frescoes were painted on the ceiling in 1880. The work is credited to W. C. Morris, a decorative sign painter who had done gilt work in buildings and designed and built sets for the Salt Lake Theater.

A February 29, 1880, article in the Salt Lake Herald, published during the progress of the painting, stated, “When finished, it will add greatly to the attractiveness of the hall, while the subjects painted on the ceiling will be a constant reminder of the history of the Church, together with some events mentioned in scripture. … The whole thing has been done in a very short space of time and materially improves the internal appearance of the hall; while it reflects great credit on the artist, Mr. W. C. Morris, and displays his talent in a new light.”

Assembly-Hall

A photograph taken by Charles Roscoe Savage of the interior of the Assembly Hall in 1882.2021 by Intellectual Reserve, Inc. All rights reserved.According to a correction published a few days later on March 4, 1880, “Paul Hammer is entitled to equal praise with [Morris], having done a large share of the figure drawing, and had a general oversight and supervision of the work.”

“The murals are one of the more interesting design features of the building,” Utt said. “We don’t see a lot of decorative work like this in Church buildings before this time. For example, we have yet to paint a temple mural when these frescoes are put on the building.”

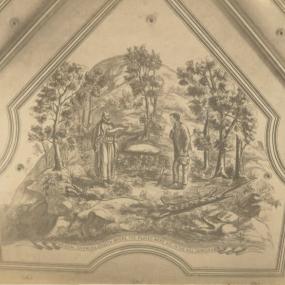

A few photographs survive of these frescoes, along with descriptions of the paintings. Three scenes from Church history were depicted: Moroni showing Joseph Smith where the gold plates were hidden in the Hill Cumorah; John the Baptist conferring the Aaronic Priesthood on Joseph Smith and Oliver Cowdery; and Peter, James and John conferring the Melchizedek Priesthood on a kneeling Joseph Smith.

Assembly-Hall

“Moroni showing Joseph where the plates were hid in the Hill Cumorah” fresco on the Assembly Hall ceiling was painted in 1880 by W.C. Morris. This photograph was taken by C. W. Carter.2021 by Intellectual Reserve, Inc. All rights reserved.Six temples appeared in the frescoes: the Kirtland, Nauvoo, St. George Utah, Manti Utah, Logan Utah and Salt Lake temples — the last of which had yet to be completed. Also depicted were images of Jesus Christ, Moses holding a scroll containing the Ten Commandments, Elijah and Elias, as well as a large beehive to represent Deseret. Above the organ was the all-seeing eye. Significant dates in Church history, such as the organization of the Church and when the pioneers arrived in the Salt Lake Valley, also appeared.

“Those murals, to me, are this great visual cue of the doctrines and the ideas that would have been important to those Latter-day Saints,” Utt said. When anyone entered the building, they would have been met with images of priesthood and temples.

What makes these paintings unusual is that “these are probably some of our earliest visual representations of these things,” she said. “We don’t have a lot of other depictions of Moroni appearing to Joseph before we get to this mural. They’re really important in the history and the evolution of Latter-day Saint art and in depicting scenes of our past.

“Unfortunately, the roof leaked.”

By about 1904, Utt said, there was enough water damage to the frescoes that they were painted over.

The Perfect Venue

Assembly-Hall

Stained glass windows are pictured in Assembly Hall in Salt Lake City on Wednesday, April 28, 2021. Photo by Kristin Murphy, courtesy of Church News.All rights reserved.“The location of the building has been a great triumph, and its great demise,” Utt said. Its position on Temple Square has afforded it protection and preservation, but as space got tight in the Salt Lake Tabernacle for general conference, overflow seating would spread to the conveniently placed building nearby.

“Within a few years of dedication, Church Headquarters really took over management of the Assembly Hall.”

It’s since had a variety of uses: it’s a gathering place for stakes in the general area beyond the Salt Lake Stake; it’s used for concerts, recitals, devotionals or events that don’t require quite the seating capacity of the Tabernacle; and it was used for early community rallying suffrage meetings.

“When you want a little more intimate experience, you come to the Assembly Hall,” Utt said.

Renovation

When it was built, the Assembly Hall was an up-to-date, modern building lit with gas chandeliers and a heating system. But over its lifespan, the building has seen repairs and renovations. Stoves were replaced by boilers, which were replaced by more modern heating systems. The roof had to be repaired in the early 1900s, the rostrum was rebuilt in the 1960s and an extensive renovation was undertaken in the 1980s.

“After 100 years, the building needed some work,” Utt said.

James F. McCrea was the architect assigned to the renovation and restoration of the building.

Assembly-Hall

Assembly Hall is pictured in Salt Lake City on Wednesday, April 28, 2021. Photo by Kristin Murphy, courtesy of Church News.All rights reserved.A portion of the basement was dug out to create dressing and practice rooms. The original wood cupola and finials were replaced with fiberglass. Visitors may note that most of the spires have a Gothic point, but one is flat because it is one of the original chimneys.

The extensive renovation, originally intended to be completed by the 150th anniversary of the Church’s formation in 1980, lasted until 1983 when President Hinckley rededicated it with other General Authorities and their wives in attendance.

A New Organ

A large reason the major renovations came about was because Tabernacle organists were frustrated with the Kimball organ installed at the turn of the 20th century and wanted to replace it with a new one for the building’s 100th anniversary.

“[Kimball organs] used a system called tubular pneumatics,” explained Robert Poll, who maintains the various organs on Temple Square. “That system was a trendy thing. And it proved to not be so effective over the long term. There were inherent flaws in the design.”

While inspections were being done to determine how best to install a new organ, “they discovered flaws in the structure of the building, in which the footings were not strong enough to hold the building,” Poll said. Extensive renovations delayed the installation of a new organ but gave opportunity to make room for practice spaces, dressing rooms and three new practice organs.

Robert L. Sipe from Austin, Texas, created the new organ. Sipe purchased components from five or six different companies who provided parts from places “as far flung as Germany,” Poll said. It consists of a large main case with three towers on each side; a smaller case, called a Rückpositive or rear positive, made of four smaller towers that sits behind the organist; a swell organ and a French-style en chamade — the horizontal reeds.

“As far as mechanical action organs go, it’s perhaps a little more flexible than some. But generally speaking, it’s a more dramatic style,” Poll said.

| Temple Square is always beautiful in the springtime. Gardeners work to prepare the ground for General Conference. © 2012 Intellectual Reserve, Inc. All rights reserved. | 1 / 2 |

Poll was hired by the Church in the fall of 1982. His first assignment was to help install the new Assembly Hall organ, working to place pipes. While many organs have pipes for display only, all of the pipes are functional in this organ.

“For the character of the room … they used copper for the base pipes,” Poll said. Using a propane torch on the pipe oxidizes the copper and makes the various colors jump out. “We call it flamed copper.”

Fetzer Architectural Woodwork, the company that contributed to building the Conference Center organ case, collaborated with the organ builder to create carvings in the white oak case.

Church architect James F. McCrea “was really big on symbolism,” Poll said, and he designed the symbols and motifs all over the organ. The First Presidency approved all symbols before they became a permanent part of the design.

The smaller case bears the date of the Church’s organization, 1830, and represents the size of the membership of the Church at the time. The main case bears the three members of the Godhead and the date of 1980, which represents the growth of the Church 150 years after its organization.

Sego lilies, which played an important part in the life of the early pioneer settlers, represent members of the Church — closed buds symbolizing new members grow into open blossoms to represent receiving the full light and knowledge of the gospel. A vine indicates growth despite the fact that sego lilies grow on single short stems. Honeybees and beehives composed of 12 rings represent the industry of the Saints.

Five-pointed stars represent Jesus Christ. The Star of David, which also appears in stained glass windows, represents the importance of the House of David through Ephraim. The letters L. D. S. appear, as do Alpha and Omega, along with rolled scrolls representing the Bible and an opened book representing the Book of Mormon.

“One of the flaws that this organ has is it’s a little difficult to accompany choirs effectively,” Poll said. “It does very well with other things; it can play a lot of literature, it adequately leads a congregation, it has a lot of brightness to it.”

The Assembly Hall Today

Visiting or attending an old building like the Assembly Hall reveals its little quirks, like a tendency for those seated on the balcony pews to unintentionally slide toward the front of the building. It all adds to the charm of the building.

“When you sit in the Assembly Hall, you know you’re in an old building; you know you’re worshipping in a place that all kinds of people have spoken and celebrated in,” Utt said. “I think that that’s what I love about that building. It’s untouched enough that you can still feel that historic sense of it.”

To schedule an in-person or virtual tour of Historic Temple Square, call 801-240-8945 or email TempleSquare@ChurchofJesusChrist.org.

Copyright 2021 Deseret News Publishing Company