- Brigham-Young

- MIP-Brigham-Young

- Brigham-Young

- Brigham-Young

- Brigham-Young

- Brigham-Young

- Brigham-Young

- d78622876cd68139022d3e3575fc64f9c1437501.jpeg

- Brigham-Young

- Brigham-Young

| Temple Square is always beautiful in the springtime. Gardeners work to prepare the ground for General Conference. © 2012 Intellectual Reserve, Inc. All rights reserved. | 1 / 2 |

This story appears here courtesy of TheChurchNews.com. It is not for use by other media.

By Ronald K. Esplin, Church History Department

After years researching the life of George Washington and publishing a multivolume biography, 20th-century scholar James Flexner chose “The Indispensable Man” as the title of his one-volume masterpiece. For Flexner, some of the circumstances of Washington’s life and service seemed beyond coincidence, almost, he hints, providential. He saw Washington as a man prepared, even preserved, to lead.

Similarly, Brigham Young was in the eyes of some not only Joseph Smith’s successor but the indispensable successor to the founding prophet of the Restoration — the man of the hour in 1844, when Joseph Smith was murdered. And with the Church on wheels in 1846 and 1847, journeying into the wilderness of the West, he became the Indispensable Pioneer, a leader with the vision and ability to hold together most of those whom Joseph had gathered and transplant them halfway across the continent to a land of new beginnings. Like Washington, he was a man prepared. Under his leadership, they flourished in their new home, establishing during his lifetime a vast Great Basin commonwealth overseen by Brigham Young from his haven in the Valley of the Great Salt Lake.

Brigham-Young

This painting depicts pioneers entering the Salt Lake Valley through Emigration Canyon in July 1847.2022 by Intellectual Reserve, Inc. All rights reserved.

What explains this success? Many in his day and since pointed to his practical abilities. American explorer and author Fitzhugh Ludlow, an acute observer and journalist, wrote at length about his visit with Brigham Young and the Saints in Salt Lake City more than a decade after its founding. Brigham Young, he said, possessed the “great American talent of un-cornerableness” (that is, the “habit of always striking on one’s feet”) “to a degree which I have never seen surpassed in any great man of any nation. He cannot be put into a position where he is at the end of his resources.” Ludlow thought President Young’s “secular astuteness” matched that of the great 19th-century European luminaries Talleyrand or Richelieu (from Fitz Hugh Ludlow, “Heart of a Continent”).

Writing about the original pioneer endeavor that brought the Saints to the Great Basin in 1847, Ludlow concluded that Young “was faith, wisdom, energy, patience, expedients, courage, enthusiasm, veritable life and soul to all the fainting Saints.” Without him, Ludlow was certain, “they never would have reached the Rocky Mountain watershed, much less the Great Salt Basin.” So much depending on Brigham Young then and after, Ludlow believed, that when the aging master left the scene, surely his grand experiment in the West would splinter and fail (see “Among the Mormons,” Atlantic Monthly, April 1864).

Though Brigham Young may have exhibited during the 1847 trek the talent and energy Ludlow described, neither Ludlow’s assessment nor that of many others who sought to understand the “secrets” of Brigham Young’s achievements understood the essence of why Brigham Young — and the pioneer endeavor —were successful.

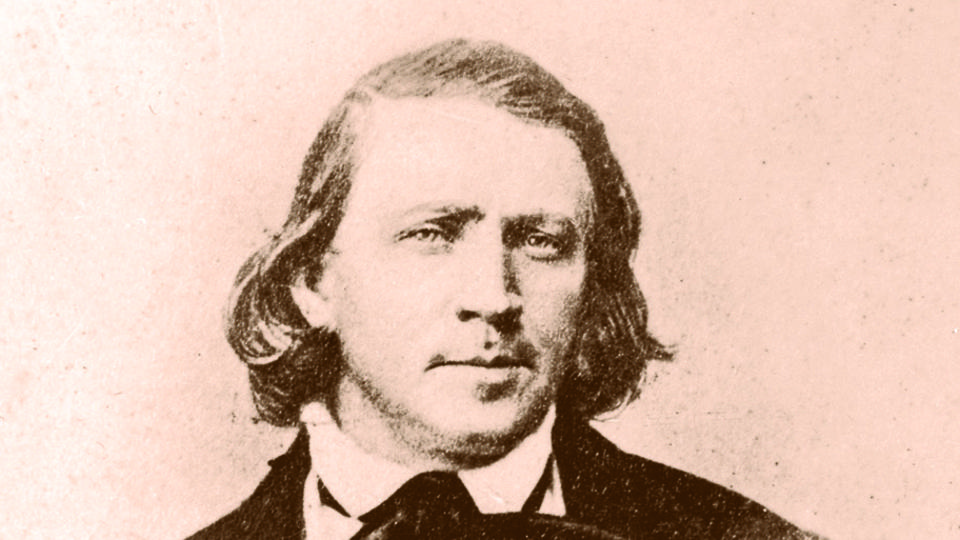

MIP-Brigham-Young

Brigham Young is about 49 years old in this 1850 photograph. He led the Latter-day Saints from Nauvoo, Illinois, to the Rocky Mountains, where he was instrumental in settling not only Salt Lake City but also cities and towns in Utah and throughout the West. He served as Church president from 1847 to 1877 and served for a time as territorial governor and Indian Agent.2016 by Intellectual Reserve, Inc. All rights reserved.

Brigham Young’s management of the trek west and establishment of hundreds of successful colonies in the heart of the continent rested on a foundation of faith in the restoration of the gospel of Jesus Christ through Joseph Smith. In Joseph he found an example to follow, and from Joseph he received the commission to oversee specific endeavors and the religious authority to successfully do so. Faith in priesthood keys to learn the mind and will of God for the Saints and knowing from Joseph and from revelation what must be done — this more than innate ability steeled him, motivated him and gave him the confidence to move forward regardless of circumstances.

Brigham himself credited years of close observation of Joseph Smith for much of his own success. Traveling with his friend and mentor to Missouri in spring 1834, a difficult trek of nearly 900 miles with too few supplies, “was the starting point of my knowing how to lead Israel” (see Brigham Young’s remarks, Salt Lake high council record, 1869–1872, Church History Library. Salt Lake high council record, 1869-1872). Then and for another decade, he never missed an opportunity to learn from Joseph. As he explained to the Saints in 1866, “An angel never watched him closer than I did, and that is what has given me the knowledge I have to day” (Oct. 8, 1866, discourse, Brigham Young Papers).

In Joseph he found the essential example that unleashed his faith and abilities in the service of the religious endeavor that grounded them both. Years of observation and service as a disciple helped Young refine innate abilities, among them unusual tenacity and the determination to do whatever circumstances required no matter the odds. “When I think of myself,” he once said, “I think just this — I have the grit in me, and I will do my duty anyhow” (Journal of Discourses 5:97; Aug. 2, 1857).

But more than innate abilities honed by discipleship and experience, President Young’s leadership rested on his conviction that he and his associates in the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles had received from Joseph all the keys and authority — and with it the commission — to move the work forward in his absence. His appeal to the Saints on August 8, 1844, seeking their sustaining vote to move forward in the absence of Joseph Smith illustrates this fusion of character and faith in his calling as an apostle, with keys and authority to lead.

Standing before the assembled Saints on August 8, 1844, he first reminded them of his record: “Here is Brigham, has his knees ever faltered? Has his lips ever quivered? Did he ever flinch before the bullets in Missouri?” But he quickly focused on other things. “Here’s the Twelve, an independent body, who have the keys of the priesthood” (Thomas Bullock minutes, Aug. 8, 1844). He presented himself and his quorum as men mentored by Joseph who held the keys. President Young’s diary notes simply, “I laid before them the order of the Church and the power of the priesthood.”

The sure knowledge that he held the keys sustained him, powering the confidence that became a hallmark of his leadership. That Joseph had given the Twelve all the keys he received from heaven, Joseph himself proclaimed in the Council of Fifty three months before his death (Council of Fifty minutes, March 26, 1844, “Joseph Smith Papers: Administrative Records, Council of Fifty Minutes”). A year later, Orson Hyde brought to the council a statement he had prepared documenting that event for members of the council to sign, attesting to Joseph’s declaration. Needing no such “sign” of authority, President Young tabled the matter. “He doesn’t care whether the world know the authority and power of the Twelve or not, when the time comes, they shall feel our power and we shall not try to prove it to them” (Council of Fifty minutes, March 25, 1845, “Joseph Smith Papers:Administrative Records, Council of Fifty Minutes”).

Brigham-Young

Eyes Westward is a statue of Joseph Smith and Brigham Young in Nauvoo, Illinois, 2022 by Intellectual Reserve, Inc. All rights reserved.

Priorities: Temple, Move West

Joseph not only prepared the Twelve to act in his absence, he set clear priorities. They intended to carry out “all the measures of Joseph.” He laid the foundation, and they would build upon it. This they declared. But they understood priorities, clarified again four months before his death: Temple first, and then find a new home for the Saints in the West. He directed the Twelve privately to find “a good location where we can remove after the temple is completed — and build a city in a day — and have a government of our own — in a healthy climate” (Joseph Smith journal, Feb. 20, 1844, Joseph Smith Collection, Church History Library). They were to find a place in the West where they could plant deep roots and flourish free from old adversaries.

Shortly after this instruction, Joseph Smith, Hyrum Smith and the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles organized the Council of Fifty, where plans for such an enterprise were confidentially developed. Plans not publicly disclosed until more than a year after Joseph Smith’s death. In contrast, the priority of completing the temple before a move from Nauvoo, Illinois, was understood by all.

Even if it meant bloodshed? Apostates urging adversaries to force them from Nauvoo before the temple was finished. That forced Brigham Young to consider the cost of completing the temple as Church leaders had publicly vowed to do. Briefly Brigham wavered, only to emerge with even greater resolve. Employing the keys provided by Joseph, “I inquired of the Lord whether we should stay here and finish the temple; the answer was we should.” Even at the risk of bloodshed, they must complete the temple, and Saints would be endowed, and then go west.In May 1845, Brigham announced to the Saints that endowments would begin in December. But not until after violence erupted in Hancock County in September did President Young and the Twelve announce to the Saints — and to the world — that they were leaving.

To Their Destiny

The announcement surprised their adversaries. Giving up so easily, before their strength had been tested? “We would rather be wronged than do wrong,” Brigham Young taught, but there was more. Now they could announce and set in motion what had long been planned. Yes, they were leaving — to their destiny. A modern prophet had foreseen a “place of safety preparing for them away toward the Rocky Mountains” (Thomas Burdick to Hyrum and Joseph Smith, Aug. 28, 1840, “Joseph Smith Papers, Documents, vol. 7”). An ancient prophet had foretold that in the last days, “the mountain of the Lord’s house shall be established in the tops of the mountains … and all nations shall flow unto it” (Isaiah 2:2-3, and Heber C. Kimball commenting on fulfillment of the prophecy, “Journal of Discourses” 10:101; discourse, Feb. 6, 1862).

An emergency it was, but not unwelcome. Brigham invited his fellow apostles to present the move to the Saints at October 1845 conference as a “glorious emergency.” Difficult though the journey may be, it was to a home long envisioned, a place prepared for them, a land of new beginnings where they could flourish.

From Iowa the next year, only a month out of Nauvoo, Brigham Young contemplated what they had left behind and what lay ahead. Rather than longing for his Nauvoo home, the best he’d ever had, or even the temple they had sacrificed so much to finish, he was looking ahead. “Do not think,” he wrote to his brother Joseph, still in Nauvoo, that “I hate to leave my house and home. No! far from that. … It looks pleasant ahead, but dark to look back” (Brigham Young to Joseph Young, March 9, 1846; Brigham Young Papers, Church History Library).

Crossing the mud of Iowa in 1846 with an imperfect organization and inexperienced pioneers presented a bigger challenge than the much longer trek in 1847 to the Rocky Mountains. Brigham is said to have lost 60 pounds in the ordeal. But he harbored no doubts about their direction or their destiny.

On March 3, 1847, a year after the note to his brother Joseph, Brigham and his brother, now with him in Winter Quarters, Nebraska, discussed the start west expected in a few weeks. The official list of provisions for the journey to the mountains worried Joseph Young. He thought 100 pounds of provisions “very little for each pioneer.” They needed food enough not only to reach their destination but to survive until harvest — or return if the crops failed. They could starve. “Brigham replied he wanted all to stay here who had not faith to go with that amount and wait till they had faith enough” (Willard Richards journal, March 3, 1847, Church History Library).

They would travel as prepared as possible. But if that amount were not enough, Brigham was certain they would not fail, for they were not alone. They were on the Lord’s errand, and He would oversee.

Download Photo

Download PhotoHome at Last!

They knew in Nauvoo that their destination was, in the words of a song sung in the March 18, 1845, meeting of the Council of Fifty, “between the (Rocky) mountains and great Pacific sea” (Council of Fifty minutes, March 18, 1845, “Joseph Smith Papers: Administrative Records, Council of Fifty Minutes”). But where in that great expanse was “the right spot” for a temple and new gathering place? “We’ll find the place which God for us prepared,” declared William Clayton’s grand pioneer hymn “Come, Come, Ye Saints,” written in Iowa in 1846. But how?

This question weighed heavily on Brigham Young while still in Nauvoo. Fasting and prayer in the temple finally provided an answer: a vision of Joseph Smith, who showed him a distinctive mountain top with a flag or ensign flying above it: “Build under the point where the colors fall and you will prosper and have peace,” said Joseph (recounted by Elder George A. Smith of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles in a discourse June 20, 1869; see “Journal of Discourses” 13:85-86).

As instructed by Brigham Young, the first pioneers to enter the valley began plowing and seeding. So late in the season, not a day could be wasted. But only after he made his way atop Ensign Peak, as he named the prominence on the north end of the valley, on July 26, 1847, could he be certain of “the right spot.” From the hilltop, he overlooked the valley from a perspective matching what he had seen in vision in Nauvoo.

On July 28, President Young gathered the pioneer company below the “table ground” he had ascended two days earlier. “I knew this spot as soon as I saw it,” he told the company. “Up there on that table ground we shall erect the Standard of Freedom” and here, at this very spot, a temple. “I know it is the spot, and we have come here according to the suggestion and direction of Joseph Smith, who was martyred” (Norton Jacobs journal, July 28, 1847, Church History Library). Another record says that he told them, “he knew that this was the place for the city for he had seen it before, and that we were now standing on the southeast corner of the Temple Block” (“Sketch of the Life of Levi Jackman,” July 28, 1847, Church History Library).

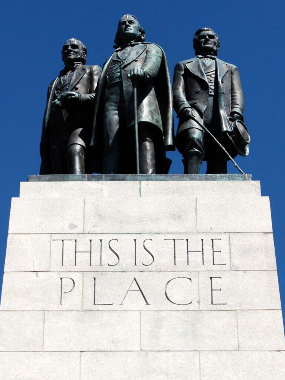

In August 1847, Brigham Young left for Winter Quarters. When he returned with his family to the valley in September 1848, he reaffirmed what he had told the pioneers the year before: “This is the place he had seen before he came here and it is the place for the Saints to gather” (Hosea Stout journal, Sept. 24, 1848, Church History Library). At the Pioneer Day celebration in 1849, Brigham’s first, he declared that the Lord “did not let us light in Nauvoo because he wanted us to come to this place. Joseph Smith and I had both seen this place years ago and that is why we are here” (Pioneer Day celebration minutes, Church History Library).

Conclusion

A steady vision born of prophecy and revelation undergirded Brigham Young’s belief that they were in 1847 on the Lord’s errand and directed essential decisions. This made him the indispensable pioneer. This was the essential foundation for his management of the trek west and establishment of hundreds of successful colonies in the heart of the continent. This guided him to find the “place prepared” (in William Clayton’s words) for a new home for the Saints and “the right spot”—the precise location for the temple, the center place of their new commonwealth.

Some spelling, grammar and punctuation standardized in quotations from early Church sources.

— Ronald K. Esplin is director of the Brigham Young Center and of the Brigham Young Papers Project. He is a general editor of the Joseph Smith Papers.