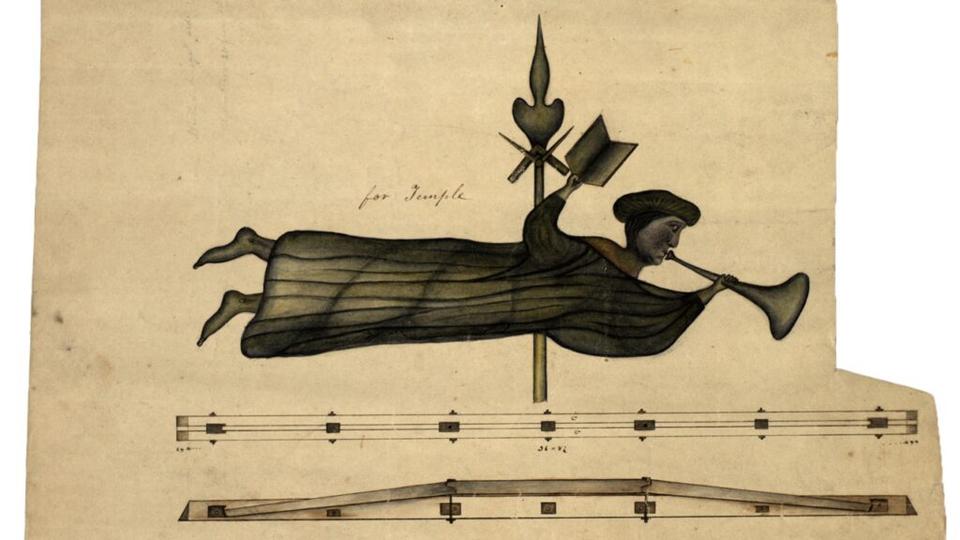

| William Weeks' architectural drawing of the angel weathervane on the Nauvoo Temple. Photo couresy of the Church History Library, courtesy of Church News. 2020 Intellectual Reserve, Inc. All Rights Reserved. | 1 / 8 |

This story appears here courtesy of TheChurchNews.com. It is not for use by other media.

By Valerie Walton, Church News

Angel Moroni standing atop the spire of a temple of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, heralding in the Restoration, seems like a natural and required finishing touch to each house of the Lord.

But Moroni’s presence on temples dotting the globe is a relatively recent addition to these sacred buildings, only becoming mostly standard in the last few decades.

“We think of angel Moroni statues as standard for temples today, but that’s because they’ve been put on temples since the 1980s [when] the vast majority of temples have been built,” said Emily Utt, historic sites curator for the Church History Department.

Utt spoke with the Church News about the origins of the angel Moroni statues and why they are featured on temples of the Church of Jesus Christ.

The first temple to feature any sort of angel was the Nauvoo Illinois Temple, which had a weathervane angel. Utt explained that in the 1840s, weathervane angels were extremely popular in the United States.

“So when Joseph Smith is building the Nauvoo temple, they put a weathervane on that temple, and it’s an angel, because that’s just what you did. That was a very common theme.”

This unnamed angel holds a trumpet to its lips and a book in its hand. It references the angel in the book of Revelation heralding in the Second Coming (Revelation 14:6).

When the Latter-day Saints arrived in Utah and began work on the Salt Lake Temple, early sketches of the temple also showed weathervane angels.

Angel Moroni Purpose 4

William Weeks' architectural drawing of the angel weathervane on the Nauvoo Temple. Photo couresy of the Church History Library, courtesy of Church News. 2020 Intellectual Reserve, Inc. All Rights Reserved.However, by the 1890s, architectural trends had shifted and it became commonplace for grand public buildings to feature statues. “So the Church is wanting to keep this angelic figure, but they decided to switch to a standing figure because that is what the architecture of the time was doing,” Utt said.

Cyrus Dallin, whose ancestors had joined the Church but left it soon after they arrived in Utah, was not a member of the Church but was commissioned to sculpt an angel statue for the Salt Lake Temple. He turned down President Wilford Woodruff’s request at first, stating that he didn’t believe in angels. But Dallin’s mother soon persuaded him to accept the commission.

“Some of those earliest sketches don’t give him a name and some of those earliest sketches called him Gabriel,” Utt said. It’s likely that Dallin’s statue was originally Gabriel, which was very common at the time for churches.

Before the statue went on the Salt Lake Temple, Church leaders went to view it in Dallin’s studio. According to Utt, “One of the Apostles said, ‘We should call him Moroni.’ And within about a week, it was no longer being called Gabriel. It was being called Moroni.”

Angel Moroni Purpose 5

Workers completing the Salt Lake Temple in 1893 pose for a picture on the spire below the Cyrus Dallin statue of the angel Moroni. Photo courtesy of the Church History Library. 2020 Intellectual Reserve, Inc. All Rights Reserved.Dallin’s Moroni was created in a neoclassical style, has flowing robes with a short cloak that leaves his arms bare and wears a cap.

Utt said that no evidence has been found explaining why it needed to be Moroni, but the name stuck thereafter.

It would be another 60 years before another statue of Moroni was placed on a temple.

The Los Angeles California Temple, which was dedicated in 1956, featured a statue created by local artist Millard F. Malin. Utt described it as looking like “an Arnold Frieberg painting.” This Moroni has Native American features, a Mayan robe, sandaled feet, a muscular build, a trumpet held by an upturned right hand and gold plates held in his left arm.

By this time, statues on buildings had fallen out of fashion, but Church leaders chose to place a Moroni statue on this temple because of what it represented.

Angel Moroni Purpose 6

Millard F. Malin stands on a ladder next to his angel Moroni statue, circa 1956. This statue was placed on the Los Angeles California Temple. Photo courtesy of Harold S. Rumel, Church History Library, courtesy of Church News.All rights reserved.“The Los Angeles temple was this landmark building,” Utt said. “It was this monument to the growth of the Church.”

Two decades later, another monumental temple received a Moroni statue, this one designed by Avard Fairbanks. The Washington D.C. Temple, which was dedicated in 1974, featured an angel Moroni statue holding gold plates like the Malin statue and robes reminiscent of the Dallin statue.

“Much like how Los Angeles is a monumental building on the west coast, the Washington D.C. Temple is this monumental building on the East Coast,” Utt said. Together with the Salt Lake Temple, these buildings “represent that the Church is here, the Church is permanent and the Church is going to stick around for a long time. And so it’s unifying to have Moroni statues on those three temples.”

Utt also noted that the temple in Washington D.C. was not its first landmark Church building to feature a statue of Moroni.

Angel Moroni Purpose 7

Avard Fairbanks' statue of the angel Moroni is seen on the Washington D.C. Temple. Photo by Izac Conn Peterson, courtesy of Church News. All rights reserved.“The Washington D.C. Ward was designed as this kind of landmark building in the heart of downtown Washington D.C.,” Utt said. It was next door to other prominent churches and nearby many embassies. “So it was this building that was designed to be a grand building in the heart of the [nation’s] capitol.”

Torleif S. Knaphus, known for his Handcart Monument on Temple Square, was commissioned to create a Moroni statue based on Dallin’s sculpture. Although they look similar from below, his sculpture has beefier arms. It was placed on the Washington D.C. Ward chapel in the early 1930s. When the building was sold, the statue was removed in 1976 and placed in the Church History Museum where it remains on display.

After the Washington D.C. Temple was dedicated, “The Church entered this era of standard temples. We were building them smaller and we were building them faster,” Utt said. Church architects searched for a way to create unity among the temples, and the Moroni statue became an easy way to make a temple identifiable.At first, the Fairbanks statue or the Knaphus statue would be scaled down and put on a temple. But then the Church commissioned Karl Quilter to not only design a new angel Moroni statue, but create one that would be easier to build and transport.

Quilter had a background in industrial design and experience building in fiberglass. “So we wanted angels that would be light and easy to transport and that could be scaled,” Utt said. These fiberglass sculptures are light enough that they can be carried by helicopter and are more economical than large, heavy bronze statues.

Commissioned in 1978, Quilter crafted two Moroni statues — the first has a wide grip on the horn, a smooth left sleeve with a straight cuff, his left arm is bent and his hand is held in a fist. The second has a tighter grip on the horn, defined wrinkles and a hem on the left sleeve and a windswept cuff.

Angel Moroni Purpose 2

Karl Quilter's angel Moroni statue at the top of the Dallas Texas Temple main front spire as seen from across the street from the east gate. Photo by Ed Woolf.All rights reserved.In 1998, Quilter redesigned his Moroni statue again, with a larger build, layered robes, an opened left hand and his body turned slightly to show more action.

The final statue was created by LaVar Wallgren. He worked extensively with Quilter and also created casts of Knaphus’ Washington D.C. Ward angel Moroni for use on other temples. Wallgren’s angel Moroni is younger than the others, wears robes with a tied sash and holds a scroll in his left hand.

This architectural trend that became a celebrated tradition is now something expected on temples. Some temples that weren’t designed with an angel Moroni statue in mind have had one added after renovations and being rededicated.

When the Church is designing and building temples, “we are not isolated,” Utt said. “The people that are designing these are drawing on their own backgrounds and their own experiences.”

From architectural trend to marking a monumental building to an easily recognizable standard for temples — whatever its purpose — angel Moroni statues are a way for Latter-day Saints to celebrate the completion of another house of the Lord and remember how the Restoration began.

Angel Moroni Purpose 1

LaVar Wallgren's white angel Moroni statue is seen on top of the Monticello Utah Temple. Photo was taken on July 26, 1998. The statue was later removed due to its poor visibility. Photo by Ravell Call, Deseret News, courtesy of Church News.All rights reserved.And, ultimately, Moroni has the same purpose that the unnamed angel weathervane had. As President Gordon B. explained in the October 1997 general conference, “The figure of Moroni, atop many of our temples, is a constant reminder of the vision of John the Revelator: ‘And I saw another angel fly in the midst of heaven, having the everlasting gospel to preach unto them that dwell on the earth, and to every nation, and kindred, and tongue, and people’ ” (“Look to the Future,” Ensign, November 1997, p.67).

Copyright 2020 Deseret News Publishing Company