| Temple Square is always beautiful in the springtime. Gardeners work to prepare the ground for General Conference. © 2012 Intellectual Reserve, Inc. All rights reserved. | 1 / 2 |

This story appears here courtesy of TheChurchNews.com. It is not for use by other media.

By Capri Baker, Church News

After a year studying indebtedness with professors Sam Hardy and Dianne Tice of Brigham Young University, Jenae Nelson has discovered the power in feeling indebted and how this separates itself from a sense of obligation.

When deciding what to research during her time in graduate school at BYU, Nelson felt inspired one day to read Luke 7, which tells of a woman who wipes the Savior’s feet with her hair and tears in gratitude. Nelson, though, realized something different about this interaction.

Following this story, Christ gives a parable of debt that took Nelson’s thoughts to Mosiah 2 on King Benjamin’s sermon of being indebted. It was then when Nelson made the connection that perhaps indebtedness plays a vital role in one’s conversion.

indebtedness

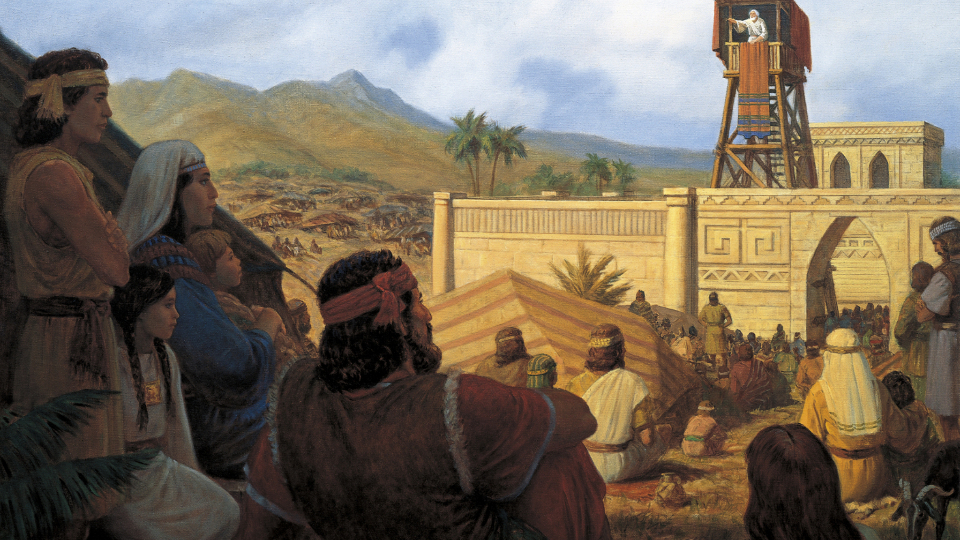

King Benjamin preaches to the Nephites.2022 by Intellectual Reserve, Inc. All rights reserved.

After conducting a survey among BYU students, Nelson was intrigued that while most did not agree with the word “indebtedness,” the response to questions about feeling unable to repay God were overwhelmingly “Yes.” In other words, while most did not claim to feel indebted, students did, in fact, feel just this.

Why is indebtedness so relevant, then? “Acknowledging your indebtedness to God cultivates gratitude. They come together. They come hand in hand,” Nelson said in a recent Church News podcast. “It’s really hard to separate them, and feelings of gratitude, obviously, make you feel good. They make you happy.”

Nelson explained that while gratitude is good, indebtedness may have more meaning. Individuals may list items they are grateful for, perhaps objects they have achieved by personal means, and this does alter the neural structures in your brain and increase happiness.

However, indebtedness connects the individual with God, making for less self-centeredness. Nelson said that rather than solely being grateful for something, being grateful to someone allows for a sense of indebtedness. She said, “Everything that you have is a gift and that changes the way that you interact with the entire world.”

In a recent study, Nelson discovered interesting results separating indebtedness and gratitude. Individuals were invited to either write a list of things they were grateful for, or write a “thank you” letter to God for what they have in their lives.

Nelson said those who simply wrote a thankful list “did not show as much prosocial giving and they also did not show as much, of what we call, empathic response. In other words, they didn’t feel as much compassion, or as much of that indebtedness.”

As a mom of four, Nelson hopes her children will grasp this idea of indebtedness for themselves. She desires that they be able to separate the ideas of feeling grateful and being a grateful person. This has impacted the ways in which she interacts with and teaches her kids, concentrating on Heavenly Father and what He has done for His children.

Indebtedness

Jenae Nelson is pictured with her family. Photo courtesy of Jenae Nelson, courtesy of Church News.All rights reserved.

To incorporate these ideas into one’s own life, Nelson encouraged others to say prayers of thanksgiving and to focus on what Heavenly Father has done for the individual, and universally, such as the Creation and the Atonement of Jesus Christ. She invited all to seek the little miracles that God gives each day and to write down these tender mercies. “Those things will really help to magnify the virtue of gratitude that we’re experiencing in our life,” she said.

Nelson said gratitude should be focused on Heavenly Father’s goodness, rather than the stuff in our possession, because He is unchanging and constant, therefore meaning that our thanks and indebtedness may be constant, as well.

“We’re eternally indebted to Him, but that is a manifestation of His love for us, that He would be willing to have this asymmetrical relationship with us, where He clearly gives way more than we give Him, but he’s OK with that, because He loves us,” said Nelson.

Even so, it is also important to recognize that God works through others, Nelson explained. This then turns gratitude outward toward those in life, strengthening relationships — whether this be teachers, parents, leaders or others.

Turning outward also results in a greater sense of giving, as was found in Nelson’s research. Students who had felt a higher level of indebtedness to God also gave more money to charity, helped the sick and needy, made more meals for those in their congregations and other such activities.

“It has been a joy,” Nelson said, “and knowing what indebtedness means — that we don’t have to shy away from this idea because it’s countercultural but that it can actually richen and deepen our religious lives — has brought me a lot of personal joy, and I hope that that can bring others joy, as well.”